International investors are biding their time on evaluating the outcome of the next US presidential election as the field of candidates gets winnowed down. The US presidential election process historically has no discernible effect on financial conditions. Financial players are sophisticated enough to know that campaign promises are not likely to become

Contents

- 1 Government Shutdown

- 2 National Security

- 3 Budget Re-Structuring

- 4 Trade

- 5 Tax Reform

- 6 Summary

- 7 Politicians and the Dollar

- 8 USDX vs. Government Shutdowns

We wonder if this time it might be different and financial markets will start responding to the US votersâ choice of president. Investors might fly off the handle at a perceived threat to the status quo. This is exactly what to expect if the extreme stance on certain issues, especially taxes and national security (i.e., war) start looking credible. Extreme stances may cause a rise in the risk premium demanded to keep global investors in the market for US assets, both stocks and bonds, and thus the dollar as well.

Overall, the US economic and financial system is both stable and resilient. It would take a major change in the systemâs infrastructure to have a big or lasting effect on financial markets. Most of the big changes being touted by candidates today are silly or impractical, but a few come close enough to the bone to pose a genuine threat.

The election will be held in November. The Republican convention that chooses the partyâs presidential candidate will take place July 18–21 in Cleveland. The Democratic convention will be held a few days later, July 25–28, in Philadelphia. As of February, Donald Trump is the most likely to become the Republican candidate and Hillary Clinton the most likely to become the Democratic Party candidate. Of the two, Trump has the most extreme proposals, while Clinton represents a continuation of President Obamaâs policy stances

Before looking at specific threats to the US financial system, itâs important to note what everyone already knows but all too often fails to keep uppermost in mindâpoliticians lie. Clinton comes under intense scrutiny so that disclosure of the smallest fib leads to a judgment of âuntrustworthyâ in polls. Trump tells more lies than any politician anyone can remember, including that his heritage is Swedish rather than German and that he saw Muslims celebrating the fall of the World Trade Center on 9/11âboth utter falsehoods. Trump said 81% of murdered whites are murdered by blacks (when 84% of murdered whites are murdered by whites). He also said the unemployment rate is not 4.9%, itâs more like 28–29% or even 35% or (he claims to have heard) 42%. Numbers that high may refer to total people not working, like children and the retired, but hardly to the

Trumpâs lies and buffoonish behavior seem not to disqualify him in the eyes of disgruntled voters, at least so far. But tolerance of lies and braggadocio may not outlast the nomination process. That means we must not ignore the lesser candidates, many of whom pose threats more chilling than Trumpâs lack of dignity and presidential demeanor.

Government Shutdown

The biggest threat to US financial asset stability is Republican candidate Ted Cruz, who led Congress to push the entire US government into shutdown in October 1–16, 2013 and threatened to do it again in November 2014. Before then, the last time the US government was shut down was 1995–96 during the Clinton administration. In both instances, the ostensible reason was the demand that deficit spending be slashed. The real reasons are more complicated and have more to do with Congress exercising power over the President and the power of individual Congressmen over the rest of Congress as well as over the President.

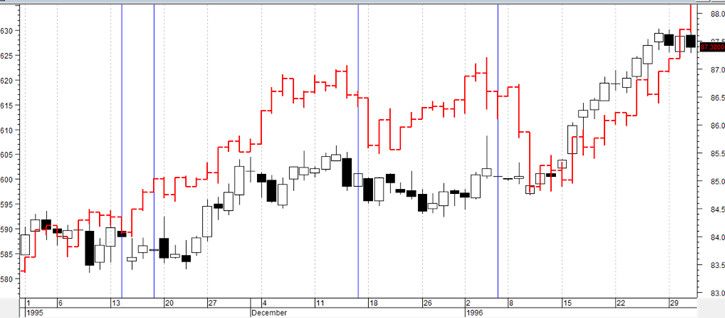

Because past government shutdowns were relatively brief, financial market players tend to see them as a nuisance rather than a crisis. During the 1995–96 episode, the dollar did not fall, nor did the S&P 500 stock index. In fact, they both went up, as you can see on the chart below. The 10-year note, already in a yield downtrend, showed no panic. Reuters reports the yield index at 5.935% on Nov 14, 1995 and 5.673% on January 8, 1996. The same thing happened in 2013. For this reason, financial market analysts donât take US government shutdowns very seriously.

But it would be a different kettle of fish if it were the President and not Congress refusing to sign a budget and thus shutting down the government. Global markets might well respond badly to President Cruz exercising executive power in this manner. It would look like dictatorial fascism. Confidence in the US and American assets would suffer. At this point in time, howeverâ

National Security

The term ânational securityâ is a proxy for ramped up military spending and

Itâs of no little interest that leading candidate Trump opposed the Iraq war and asserts the US must not only win any war, but also win the peace. He says if the US canât do both, it needs to stay out. This contradicts his other statements about bombing the Iraqi oilfields (and any civilians who happen to be around) to defeat ISIS. Trump has also said mutually exclusive things about âtaking onâ Russian leader Putin. In December 2015, Putin praised Trump, a strange event. Nobody can remember a world leader praising a presidential candidate. Itâs likely that because both men are raging narcissists, they actually do understand one another.

If we accept the view that Putinâs overriding goal is to restore the grandeur and power of the

Likely Democratic candidate Clinton is less militaristic than the Republicans generally. Having been Secretary of State under President Obama, Clinton is already fully briefed on what the US can realistically hope to achieve. Clinton has not proposed any major changes in the military budget or mix of military and

That is a task taken by Senator Bernie Sanders, who voted against the Iraq war and would like to see more diplomacy and less military action. Sanders proposes cutting the defense budget, although he has not named a specific amount, on the grounds that former President Eisenhowerâs worry about the â

If Sanders gets the Democratic Party nomination, the immediate effect would be a

Budget

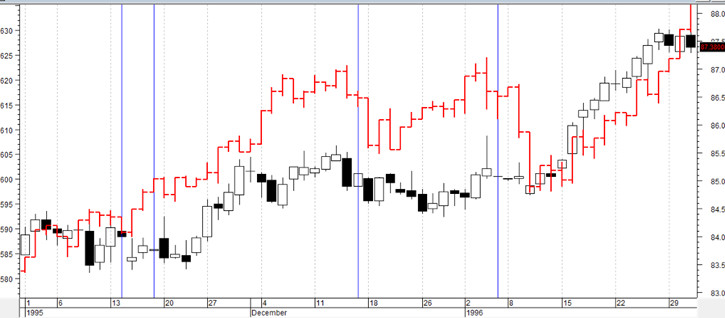

Except for 1969 and four years around 2000, the US federal budget has been in deficit since 1965. In fiscal 2015, the deficit contracted to $439 billion, the lowest level since 2008, on

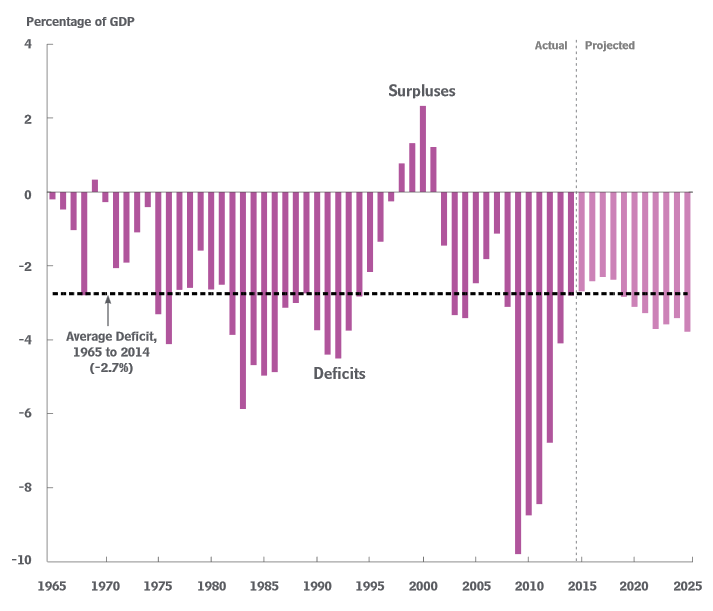

The US has two budget problemsâthe composition of the deficit and the cumulative debt burden. Both aspects of the US budget reflect an issue that no other G7 or G20 country facesâthe cost of military spending. The US spends more on military spending than the next ten countries combined.

Politicians and voters alike are confused on the subject of the US as âworld leader.â Critics say the US has no business appointing itself the leader of the free world, and yet they expect the US to rush to the rescue when their own

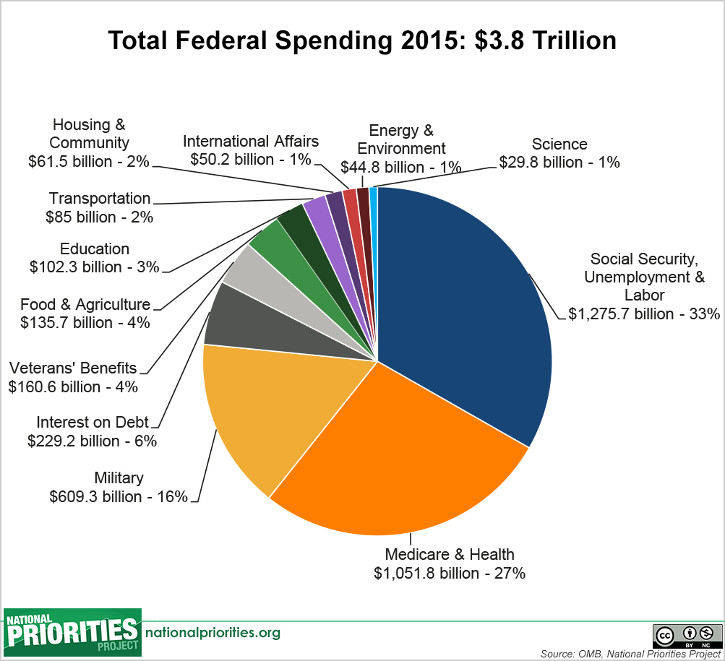

Conflicted emotions about the US as military world leader springs to life when it comes to political talk about the budget deficit. This is because the budget has two componentsâmandatory spending and discretionary spending (the third component is interest on the debt). Mandatory spending is largely social spending on public pensions (Social Security), health care for the retired (Medicare), and unemployment benefits. Mandatory spending also includes a large portion for the military. All other spending programs pale by comparison.

The 2015 fiscal year budget was $3.8 trillion or 21% of GDP. Of that total, $1.1 trillion was discretionary spending, i.e., programs selected and specifically funded by Congress. To the portion of the budget mandated for military spending, Congress added an additional $598.5 billion in discretionary spending, or 54% of discretionary spending, on top of the amount already existing under mandatory spending. But while defense spending may be 54% of discretionary spending, itâs 16% of total spending, according to politifact.com. The lionâs share of total spending does go to Health and Human Resources and Social Security.

The perennial political debate between the two parties has the Republicans seeking to expand military discretionary spending while cutting mandatory social spending, and Democrats defending or wanting to enlarge social spendingâwhile not necessarily also wanting to cut military spending at the same time. Republicans want deficits to fall while Democrats are seen as not much caring about the deficit level. This may not be accurate or fair, but itâs the common perception.

Many of the Republican candidates, including Trump, claim to favor an amendment to the Constitution that would require a balanced budget. Trump also says he would not cut social programs. The only logical deduction from both positions is either a very big cut in defense spending or a tax hike for everyone. Since a cut in defense spending would never pass in Congress, that means a Trump presidency calls for a tax increase.

A Constitutional amendment requiring a balanced budget is not likely but not impossible. And it would be a

Conventional wisdom has it that deficits contribute to inflation and thus confidence in the US economy and financial system would rise dramatically if we had a balanced budgetâas we see in Germany. In fact, the single mandate of the European Central Bank is to control inflation, while the US Fed has a dual mandate that adds keeping employment at a good level. A balanced budget amendment would be

Trade

Leading Republican candidate Trump has offered up many outrageous proposals, including building a wall along the Mexican border against illegal immigrants and making Mexico pay for it. He would also ban all Muslim travelers and immigrants, and other absurd (and unconstitutional) measures. Even his followers admit that much of what Trump promises is not possible or legal, but donât care. He has tapped into a vein of anger among voters that government is not delivering what the voters have asked for.

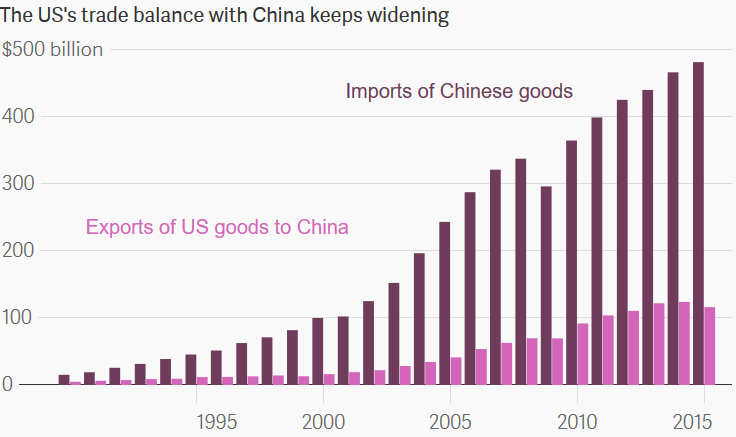

After the wall on the Mexican border, Trumpsâ biggest promise is to write a new trade deal with China, as well as repudiate the North American Free Trade deal and the

The outcome would be to raise the price of

The trade imbalance with China is indeed a point of contention. We get cheap socks and phones, and China gets dollars with which to buy Treasuries and US companies. The trade deficit has grown from $83.8 billion in 2000 to $365.7 billion in 2015.

A giant tariff on US imports from China would not immediately result in old factories

Voters have been told since the days of Ronald Reagan that free trade benefits everyone. But faith in

Tax Reform

The single thing that would boost the US economy the most would be corporate tax reform. The tax is so highâ35%âthat companies are pretending to move overseas (âinversionâ), while others have such devious tax lawyers that they pay no US tax at all, such as General Electric. Since 2012, twenty major companies have moved overseas to dodge taxes, including Burger King (Canada) and Pfizer (Ireland). Major multinational corporations spend as much on lawyers and accountants finding ways to avoid or defer taxation as they do research and development.

Itâs stupid and cannot, seemingly, be fixed; the current crop of presidential candidates all declare they want to throw out the current tax code and start over. But as a practical matter, you canât throw out the baby with the bath water. You need agreement on the new tax code for corporations before you can transition from the old one, and itâs too big a job for Congress to agree on. Congressâs outright failure to solve the corporate tax problem is a key reason its approval rating is lower than 10%.

Clinton would impose an exit tax, which hardly solves the problem, and Trump would cut the corporate tax rate to 15%. The probability of a corporate tax cut is higher than the probability of getting agreement on an exit tax.

As for personal tax rates, every single candidate tries to pander to the voter by promising tax cutsâexcept Sanders. Sanders would raise everyoneâs personal tax rate, with progressively higher rates on higher incomes, while taxing capital gains as ordinary income. This is something the financial markets understand all too well and would respond to immediately if Sanders gets the nominationâa massive

Sanders also promises an economically unjustified

Sanders also promises free university education for all but underestimates the cost, and proposes Congressional control of the Federal Reserve. This would take the form, for example, of barring the Fed from raising interest rates if unemployment is above 4%.

Giving Congress control of the Fed is unthinkable even among the most severe Fed critics. The Fed is the only institution in public life today that has independence from political interference and thus a modicum of respect. The financial sector that actually understands the role of the Fed would fight

Sanders is not likely to win the Democratic party nomination in July, but if he were to win, we can expect two outcomes: first, at least some

Summary

To conclude, presidential candidates make promises they cannot keep. The president is not a dictator who can unilaterally impose new laws. Congress and the judiciary serve as a check on executive power (and vice versa).

Newly elected presidents hardly ever achieve their campaign promises, and certainly not in the first 100 days. Franklin D. Roosevelt was the one exception, and that was over 80 years ago in 1933. Roosevelt got fifteen major bills through Congress in the first 100 days, including the Emergency Banking Act and the bill ending Prohibition. Nobody else has come even close, unless you want to include the Civil Rights Act in 1964 under Lyndon Johnson, who at that time had not actually been elected but was fulfilling the job started by President John Kennedy in 1963 before he was assassinated.

As a rule, the first year of a new presidentâs administration is accompanied by rising equities. That may not hold true if itâs a

If these two are the official candidates, former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg has said he will consider entering the race as an independent candidate. Independents have a bad record in the US. In recent memory we have had a Texas millionaire, Ross Perot, who dropped out of the 1992 election, and consumer rights activist Ralph Nader, who is thought to have spoiled the 2000 election by taking votes from Democrat Al Gore, thus favoring Republican George W. Bush.

But Bloomberg may be a different kind of animal. For one thing, Perot and Nader started out as

As for the other candidates, Marco Rubio is perceived as lacking poise and being too green. Dr. Ben Carson will fall out from lack of government experience (and believing the Egyptian pyramids were built to store grain). He is not even listed in the betting tanks. As noted above, Jeb Bush is probably overly contaminated by his acceptance of brother George Wâs

Betting websites

Bottom line, the consensus that Trump will become the next US president seems outlandish and yet not out of the question. Of the key issues, Trump is basically right about taking China to task on trade, about raising taxes on the rich and trying to balance the budget, and about using military resources wisely, even if his impulsive style is worrisome.

Politicians and the Dollar

Noted above is that a Cruz presidency would drive investors away from the dollar because of suspicions he would shut down the government to get his way. A Clinton presidency would likely be a continuation of the Obama administration, with a low level of militarism but also no change on taxes. To be fair, very little that a new presidential administration does can affect the dollar. The key factor influencing the dollar is interest rates, both the trend in the USâ own rates and the differential with other major issuers of sovereign debt. That makes the key player the Federal Reserve, not the president.

But Trump has some ideas that would likely cause a dollar

Trumpâs idea of imposing tariffs on China is the most risky. As noted, it would make goods more costly for Americans but it also invites retaliation in the form of China potentially dumping a portion of its reserves held in US dollars, about $1.264 trillion as of the latest official count (November 2015). If the supply of Treasuries were to increase by that much over a short period, the price would get driven down (and the yield up). To replace Treasuries with notes and bonds denominated in another currency, China would be a massive seller of dollars. The first announcement of a US tariff would almost certainly set off a general dollar

Another potential political

Repatriation entails selling the foreign currencies in which overseas profits are held and buying dollars. In the end, companies repatriated $312 billion, much of it late in the year. But this is a small sum in the context of the overall FX market of over $1 trillion per day. Still, there were some weeks when the repatriation was seen as a dollar driver.

USDX vs. Government Shutdowns

Ahead of the government shutdown in 1995, the dollar index had already fallen hard in September, but not because of the looming shutdown. The Federal Reserve had cut the Fed funds rate from 6.0% to 5.75% in July, and the dollar was sold off in September in anticipation of another cut at the September FOMC. That cut didnât come, however, until December 19 (to 5.50%). Meanwhile, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed over 5000 for the first time on November 20. Stock market participants almost always increase equity holdings when rates are falling. Expectations about the Fed were the driver of the dollar that fall, not the shutdown. The dollar index bottomed in late October and proceeded higher to surpass the September high by

The more recent government shutdown was October 1–16, 2013. Again, analysts were surprised that it had less effect on the dollar than other events. For one thing, mandated government spending cuts (âsequesterâ) had already started in March. Also in March, the Cyprus sovereign debt crisis hit, ending in a depositorsâ

About the author: Barbara Rockefeller is an international economist with a focus on foreign exchange. She has worked as a forecaster, trader, and consultant at Citibank and other financial institutions, and currently publishes daily reports on foreign exchange for RTS. Rockefeller is the author of The Baby Boomer Survival Guide (Humanix, 2014), The Foreign Exchange Matrix (Harriman House, 2013), Technical Analysis for Dummies (For Dummies, 2004), 24/7 Trading Around the Clock, Around the World (John Wiley & Sons, 2000), The Global Trader (John Wiley & Sons, 2001), and How to Invest Internationally, published in Japan in 1999.